What is Testicular Cancer?

Cancer starts when cells in the body begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancerous and can spread to other areas of the body. To learn more about how cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?

Cancer that starts in the testicles is called testicular cancer. To understand this cancer, it helps to know about the normal structure and function of the testicles.

Testicles (also called the testes; a single testicle is called a testis) are part of the male reproductive system. These 2 organs are each normally a little smaller than a golf ball in adult males and are contained within a sac of skin called the scrotum. The scrotum hangs beneath the base of the penis.

Testicles have 2 main functions:

They make male hormones (androgens), such as testosterone.

They make sperm, the male cells needed to fertilize a female egg cell to start a pregnancy.

Sperm cells are made in long, thread-like tubes inside the testicles called seminiferous tubules. They are then stored in a small coiled tube behind each testicle, called the epididymis, where they mature.

During ejaculation, sperm cells are carried from the epididymis through the vas deferens to seminal vesicles, where they mix with fluids made by the vesicles, prostate gland, and other glands to form semen. This fluid then enters the urethra, the tube in the center of the penis through which both urine and semen leave the body.

The testicles are made up of several types of cells, each of which can develop into one or more types of cancer. It is important to distinguish these types of cancers from one another because they differ in how they are treated and in their prognosis (outlook).

Germ cell tumors

More than 90% of cancers of the testicle develop in special cells known as germ cells. These are the cells that make sperm. The 2 main types of germ cell tumors (GCTs) in men are:

Seminomas

Non-seminomas, which are made up of embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and/or teratoma

Doctors can tell what type of testicular cancer you have by looking at the cells under a microscope.

These 2 types occur about equally. Many testicular cancers contain both seminoma and non-seminoma cells. These mixed germ cell tumors are treated as non-seminomas because they grow and spread like non-seminomas.

Seminomas

Seminomas tend to grow and spread more slowly than non-seminomas. The 2 main subtypes of these tumors are classical (or typical) seminomas and spermatocytic seminomas. Doctors can tell them apart by how they look under the microscope.

Classical seminoma: More than 95% of seminomas are classical. These usually occur in men between 25 and 45.

Spermatocytic seminoma: This rare type of seminoma tends to occur in older men. The average age of men diagnosed with spermatocytic seminoma is about 65. Spermatocytic tumors tend to grow more slowly and are less likely to spread to other parts of the body than classical seminomas.

Some seminomas can increase blood levels of a protein called human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). HCG can be detected by a simple blood test and is considered a tumor marker for certain types of testicular cancer. It can be used for diagnosis and to check how the patient is responding to treatment.

Non-seminomas

These types of germ cell tumors usually occur in men between their late teens and early 30s. The 4 main types of non-seminoma tumors are:

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk sac carcinoma

Choriocarcinoma

Teratoma

Most tumors are a mix of different types (sometimes with a seminoma component as well), but this doesn’t change the general approach to the treatment of most non-seminoma cancers.

Embryonal carcinoma: This type of non-seminoma is present to some degree in about 40% of testicular tumors, but pure embryonal carcinomas occur only 3% to 4% of the time. When seen under a microscope, these tumors can look like tissues of very early embryos. This type of non-seminoma tends to grow rapidly and spread outside the testicle.

Embryonal carcinoma can increase blood levels of a tumor marker protein called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), as well as human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG).

Yolk sac carcinoma: These tumors are so named because their cells look like the yolk sac of an early human embryo. Other names for this cancer include the yolk sac tumor, endodermal sinus tumor, infantile embryonal carcinoma, or orchidoblastoma.

This is the most common form of testicular cancer in children (especially in infants), but pure yolk sac carcinomas (tumors that do not have other types of non-seminoma cells) are rare in adults. When they occur in children, these tumors usually are treated successfully. But, they are of more concern when they occur in adults, especially if they are pure. Yolk sac carcinomas respond very well to chemotherapy, even if they have spread.

This type of tumor almost always increases blood levels of AFP (alpha-fetoprotein).

Choriocarcinoma: This is a very rare and aggressive type of testicular cancer in adults. Pure choriocarcinoma is likely to spread rapidly to distant organs of the body, including the lungs, bones, and brain. More often, choriocarcinoma cells are present with other types of non-seminoma cells in a mixed germ cell tumor. These mixed tumors tend to have a somewhat better outlook than pure choriocarcinomas, although the presence of choriocarcinoma is always a worrisome finding.

This type of tumor increases blood levels of HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin).

Teratoma: Teratomas are germ cell tumors with areas that, under a microscope, look like each of the 3 layers of a developing embryo: the endoderm (innermost layer), mesoderm (middle layer), and ectoderm (outer layer).

Pure teratomas of the testicles are rare and do not increase AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) or HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) levels. More often, teratomas are seen as parts of mixed germ cell tumors.

There are 3 main types of teratomas:

Mature teratomas are tumors formed by cells similar to cells of adult tissues. They rarely spread to nearby tissues and distant parts of the body. They can usually be cured with surgery, but some come back (recur) after treatment.

Immature teratomas are less well-developed cancers with cells that look like those of an early embryo. This type is more likely than a mature teratoma to grow into (invade) surrounding tissues, to spread (metastasize) outside the testicle, and to come back (recur) years after treatment.

Teratomas with somatic-type malignancy are very rare cancers. These cancers have some areas that look like mature teratomas but have other areas where the cells have become a type of cancer that normally develops outside the testicle (such as a sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, or even leukemia).

Carcinoma in situ of the testicle

Testicular germ cell cancers can begin as a non-invasive form of the disease called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or intratubular germ cell neoplasia. In testicular CIS, the cells look abnormal under the microscope, but they have not yet spread outside the walls of the seminiferous tubules (where sperm cells are formed). Carcinoma in situ doesn’t always progress to invasive cancer.

It is hard to find CIS before it does become invasive cancer because it generally does not cause symptoms and often does not form a lump that you or the doctor can feel. The only way to diagnose testicular CIS is to have a biopsy (a procedure that removes a tissue sample and looks at it under a microscope). Some cases are found incidentally (by accident) when a testicular biopsy is done for another reason, such as infertility.

Experts don’t agree about the best treatment for CIS. Since CIS doesn’t always become invasive cancer, many doctors in the United States consider observation (watchful waiting) to be the best treatment option.

When the CIS of the testicle becomes invasive, its cells are no longer just in the seminiferous tubules but have grown into other structures of the testicle. These cancer cells can then spread either to the lymph nodes (small, bean-shaped collections of white blood cells) through lymphatic channels (fluid-filled vessels that connect the lymph nodes), or through the blood to other parts of the body.

Stromal tumors

Tumors can also develop in the supportive and hormone-producing tissues, or stroma, of the testicles. These tumors are known as gonadal stromal tumors. They make up less than 5% of adult testicular tumors but up to 20% of childhood testicular tumors. The 2 main types are Leydig cell tumors and Sertoli cell tumors.

Leydig cell tumors

These tumors develop from the Leydig cells in the testicle that normally make male sex hormones (androgens like testosterone). Leydig cell tumors can develop in both adults and children. These tumors often make androgens (male hormones) but sometimes produce estrogens (female sex hormones).

Most Leydig cell tumors are benign. They usually do not spread beyond the testicle and are cured with surgery. But a small portion of Leydig cell tumors spread to other parts of the body and tend to have a poor outlook because they usually do not respond well to chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Sertoli cell tumors

These tumors develop from normal Sertoli cells, which support and nourish the sperm-making germ cells. Like the Leydig cell tumors, these tumors are usually benign. But if they spread, they usually don’t respond well to chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Secondary testicular cancers

Cancers that start in another organ and then spread to the testicle are called secondary testicular cancers. These are not true testicular cancers – they are named and treated based on where they started.

Lymphoma is the most common secondary testicular cancer. Testicular lymphoma occurs more often than primary testicular tumors in men older than 50. The outlook depends on the type and stage of lymphoma. The usual treatment is surgical removal, followed by radiation and/or chemotherapy.

In boys with acute leukemia, the leukemia cells can sometimes form a tumor in the testicle. Along with chemotherapy to treat leukemia, this might require treatment with radiation or surgery to remove the testicle.

Cancers of the prostate, lung, skin (melanoma), kidney, and other organs also can spread to the testicles. The prognosis for these cancers tends to be poor because these cancers have usually spread widely to other organs as well. Treatment depends on the specific type of cancer.

The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team

Testicular Cancer Treatment

In recent years, a lot of progress has been made in treating testicular cancer. Surgical methods have been refined, and doctors know more about the best ways to use chemotherapy and radiation to treat different types of testicular cancer.

After the cancer is diagnosed and staged, your cancer care team will discuss treatment options with you.

Depending on the type and stage of the cancer and other factors, treatment options for testicular cancer can include:

Surgery

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy (chemo)

High-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplant

In some cases, more than one type of treatment might be used.

You may have different types of doctors on your treatment team, depending on the stage of your cancer and your treatment options. These doctors may include:

A urologist: a surgeon who specializes in treating diseases of the urinary system and male reproductive system

A radiation oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer with radiation therapy

A medical oncologist: a doctor who treats cancer with medicines, such as chemotherapy

Many other specialists might be involved in your care as well, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, physical therapists, social workers, and other health professionals. See Health Professionals Associated With Cancer Care for more on this.

It’s important to discuss all of your treatment options, as well as their possible side effects, with your doctors to help make the decision that best fits your needs. (See What should you ask your doctor about testicular cancer? for some questions to ask.)

When time permits, getting a second opinion is often a good idea. It can give you more information and help you feel good about the treatment plan you choose.

Where you are treated is important. There is no substitute for experience. You have the best chance for a good outcome if you go to a hospital that treats many testicular cancer patients.

Thinking about taking part in a clinical trial

Clinical trials are carefully controlled research studies that are done to get a closer look at promising new treatments or procedures. Clinical trials are one way to get state-of-the-art cancer treatment. In some cases, they may be the only way to get access to newer treatments. They are also the best way for doctors to learn better methods to treat cancer. Still, they are not right for everyone.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for you, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials. You can also call the American cancer society clinical trials matching service at (800) 303-5691 for a list of studies that meet your medical needs.

Considering complementary and alternative methods

You may hear about alternative or complementary methods that your doctor hasn’t mentioned to treat your cancer or relieve symptoms. These methods can include vitamins, herbs, special diets, or other methods, such as acupuncture or massage, to name a few.

Complementary methods refer to treatments that are used along with your regular medical care. Alternative treatments are used instead of a doctor’s medical treatment. Although some of these methods might be helpful in relieving symptoms or helping you feel better, many have not been proven to work. Some might even be dangerous.

Be sure to talk to your cancer care team about any method you are thinking about using. They can help you learn what is known (or not known) about the method, which can help you make an informed decision.

Help to get through cancer treatment

Your cancer care team will be your first source of information and support, but there are other resources for help when you need it. Hospital- or clinic-based support services are an important part of your care. These might include nursing or social work services, financial aid, nutritional advice, rehab, or spiritual help.

The American Cancer Society also has programs and services, including rides to treatment, lodging, support groups, and more, to help you get through treatment. Call the National Cancer Information Center at (800) 227-2345 and speak with one of the trained specialists on call 24 hours a day, every day.

What Is Prostate Cancer?

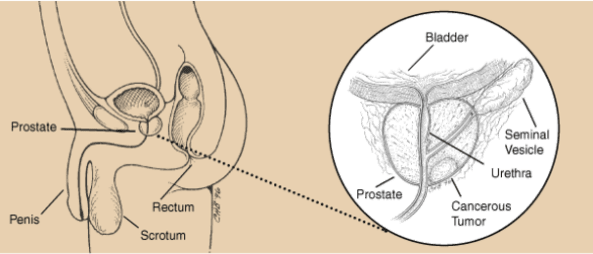

Prostate cancer begins when cells in the prostate gland start to grow uncontrollably. The prostate is a gland found only in males. It makes some of the fluid that is part of semen.

The prostate is below the bladder and in front of the rectum. The size of the prostate changes with age. In younger men, it is about the size of a walnut, but it can be much larger in older men.

Just behind the prostate are glands called seminal vesicles that make most of the fluid for semen. The urethra, which is the tube that carries urine and semen out of the body through the penis, goes through the center of the prostate.

Types of prostate cancer

Almost all prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas. These cancers develop from the gland cells (the cells that make the prostate fluid that is added to the semen).

Other types of prostate cancer include:

- Sarcomas

- Small cell carcinomas

- Neuroendocrine tumors (other than small cell carcinomas)

- Transitional cell carcinomas

These other types of prostate cancer are rare. If you have prostate cancer it is almost certain to be an adenocarcinoma.

Some prostate cancers can grow and spread quickly, but most grow slowly. In fact, autopsy studies show that many older men (and even some younger men) who died of other causes also had prostate cancer that never affected them during their lives. In many cases neither they nor their doctors even knew they had it.

Possible pre-cancerous conditions of the prostate

Some research suggests that prostate cancer starts out as a pre-cancerous condition, although this is not yet known for sure. These conditions are sometimes found when a man has a prostate biopsy (removal of small pieces of the prostate to look for cancer).

Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN)

In PIN, there are changes in how the prostate gland cells look under a microscope, but the abnormal cells don’t look like they are growing into other parts of the prostate (like cancer cells would). Based on how abnormal the patterns of cells look, they are classified as:

Low-grade PIN: the patterns of prostate cells appear almost normal

High-grade PIN: the patterns of cells look more abnormal

PIN begins to appear in the prostates of some men as early as in their 20s.

Many men begin to develop low-grade PIN when they are younger but don’t necessarily develop prostate cancer. The possible link between low-grade PIN and prostate cancer is still unclear.

If high-grade PIN is found in your prostate biopsy sample, there is about a 20% chance that you also have cancer in another area of your prostate.

Proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA)

In PIA, the prostate cells look smaller than normal, and there are signs of inflammation in the area. PIA is not cancer, but researchers believe that PIA may sometimes lead to high-grade PIN, or perhaps to prostate cancer directly.

TC Self-Check Guide

The best time for you to examine your testicles is during or after a bath or shower when the skin of the scrotum is relaxed.

Hold your penis out of the way and examine each testicle separately.

Hold your testicle between your thumbs and fingers with both hands and roll it gently between your fingers.

Look and feel for any hard lumps or nodules (smooth rounded masses) or any change in the size, shape, or consistency of your testicles.

It’s normal for one testicle to be slightly larger than the other, and for one to hang lower than the other. You should also be aware that each normal testicle has a small, coiled tube called the epididymis that can feel like a small bump on the upper or middle outer side of the testis. Normal testicles also contain blood vessels, supporting tissues, and tubes that carry sperm. Some men may confuse these with abnormal lumps at first. If you have any concerns, ask your doctor.